Below are our active areas of research along with linked representative publications. Check out the Publications tab to find more articles from the lab.

Overall, our lab is primarily interested in the processes that support the brief retention of information in working memory (WM), how these processes impact and interact with later retrieval from long-term memory (LTM), and how healthy older age impacts the interaction between these memory systems (see Bartsch et al., 2024 and Loaiza, 2024 for a couple of big-picture reviews).

How does attention help to keep information active in working memory?

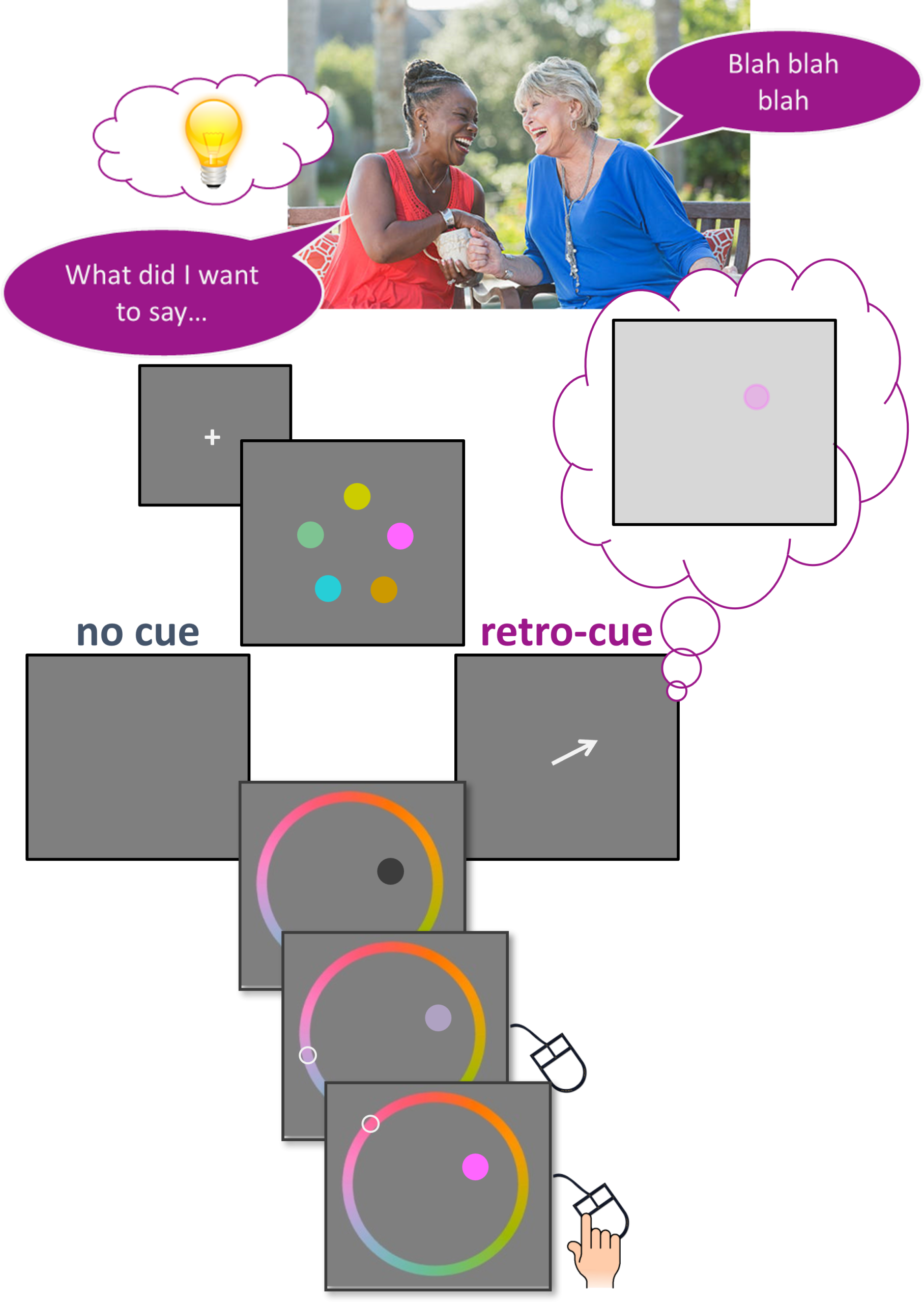

We are often in situations where we need to keep different goals active in mind to complete a task, such as having a chat with a friend: We have to focus on what our friend is saying, but also shift an arising thought to the “back of your mind” until it’s your turn to talk. How often have you had the experience of trying to refocus on what you just had in mind a moment ago, but now seems (perhaps temporarily) lost? This shifting of information in and out of one’s focus of attention, better known as refreshing (see Camos et al., 2018 for review), is a mechanism that is often asserted to be crucial to WM functioning. Research from our lab using variants of the retro-cue paradigm shown in the figure coheres with the notion that guiding attention to information that is no longer perceptually present enhances WM performance (Goldenhaus-Manning et al., 2024), but it is probably not the same thing as simply moving your eyes to where the information used to be (Loaiza & Souza, 2022). Moreover, younger and healthy older adults are just as likely to benefit from focusing or switching their attention to to-be-tested memory items (Loaiza & Souza, 2018), but healthy older adults disproportionately struggle to retain those benefits after being distracted (Loaiza & Souza, 2019). There is still a great deal of work to be done to understand exactly how this is all accomplished. For example, where does that “lost” information go — is it completely inactive in long-term memory or is there some “in-between” state? (Chao et al., 2023). And what exactly is attention doing to augment the information in WM, and how are those effects distinguishable from other mechanisms like simply repeating the information in our head over and over (i.e., rehearsal; Loaiza & McCabe, 2013)? These and other questions are fruitful avenues of research in our lab!

How do working memory processes impact later retrieval from long-term memory?

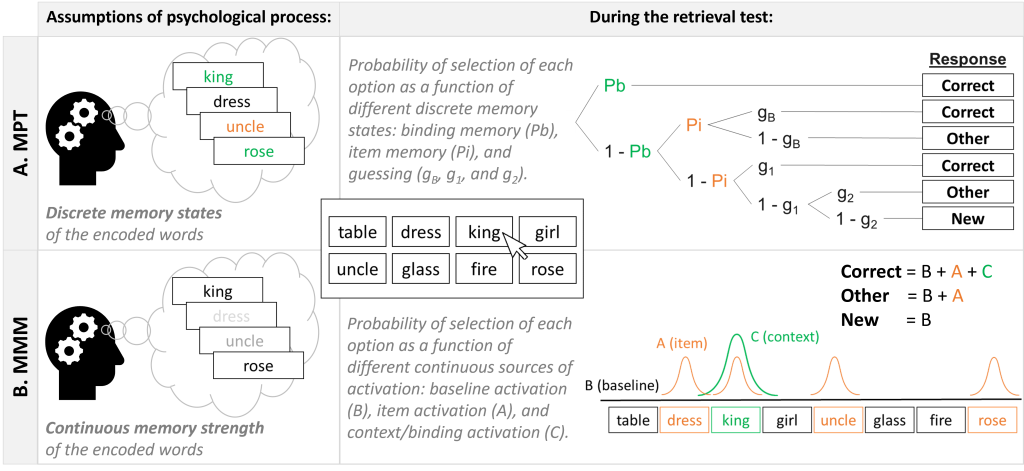

Our research also concerns how the processes that allow us to keep information active in WM may later affect retrieval from LTM. For example, what about what you are doing during your conversation with your friend makes it more likely that you’ll remember it later on? If you read the section above about attention in WM, perhaps your mind went straight to a hypothesis many researchers have had: Maybe refreshing impacts LTM! Unfortunately, the literature is quite mixed on this, even from our own lab: We have made this argument (Loaiza & Borovanska, 2018; Loaiza et al., 2021; Loaiza & McCabe, 2012; Loaiza et al., 2015) yet we have also shown evidence against it (Jarjat et al., 2021; Loaiza et al., 2023). Of course, there are other proposed WM processes that may also impact LTM, such as elaboration (e.g., forming images or links between studied information; Loaiza & Lavilla, 2021) and consolidating associations that allow younger and healthy older adults alike to retain the information in the long-term (Bartsch et al., 2019). Using cognitive modeling methods like those visualized below, we have shown that uninterrupted active maintenance in WM is particularly important to retaining those associations over time (Loaiza & Souza, 2024). The next step is to determine precisely what that active maintenance entails!

How does long-term memory faciltiate/interfere with working memory?

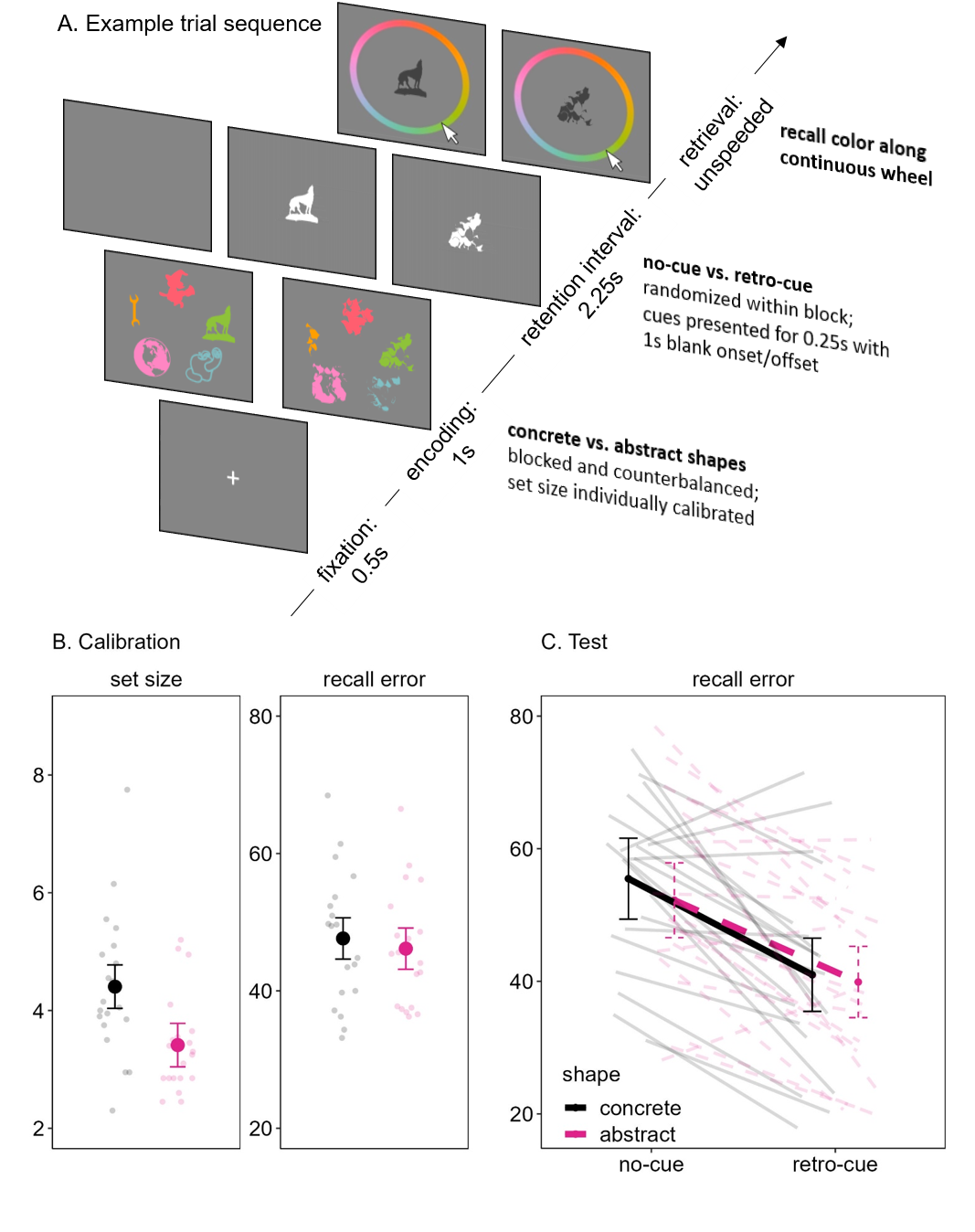

Another major topic of research in our lap concerns the reverse direction of WM-LTM interaction: How does what we already have stored in LTM influence WM functioning? Keeping with the conversation example above, imagine that your friend was telling you about the minutia of her astrophysics research — she may be speaking the same language as you, but unless you already have knowledge of the topic, it will be hard to keep up. But what exactly is going on that makes it so difficult? One way that we can investigate this is to manipulate the meaningfulness of the memory items to our prior knowledge, as in the figure. Our research has shown mixed findings regarding whether prior knowledge facilitates attention in WM (Loaiza et al., 2024; Loaiza et al., 2015), but we have shown that it greatly facilitates binding information together, especially in health older age (Jarjat et al., 2021; Loaiza & Srokova, 2020). On the flip side, our prior knowledge does not always come in handy if it’s outdated or irrelevant to what we’re doing. We have explored this by investigating how prior knowledge can also interfere with working memory (Bartsch et al., under review; Loaiza et al., 2025) and the processes that allow effective updating of information to avoid being misinformed (Kemp et al., 2022; Kemp et al., 2024; Loaiza & von Bastian, in prep). There is still so much to learn about how prior knowledge in LTM can both facilitate and interfere with our ability to keep information active in WM, especially when it comes to using that information to make the best decisions in everyday life.